Batteries - where PV was five years ago

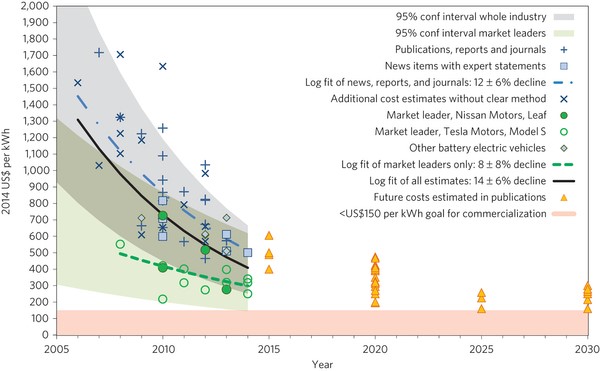

Batteries are improving fast. A new article in Nature Climate Change suggests that the cheapest lithium ion batteries (the sort that powers your phone and your Tesla) are now costing little more than $250 a kilowatt hour, down from at least three times this level five years ago. By the end of this year, some have recently suggested that the cost may be as low as $150/kWh, although this is not shown in the chart below. This would imply that a battery pack in a car with 200 miles range might cost as little as $8,000/£5,500.

Source: Nykvist and Nillson, Nature Climate Change, March 25th 2015

Even more significantly for the battery industry, this price would mean that electricity storage would fall in price to less than the cost of building rarely used ‘peaker’ power plants to meet occasional spikes in electricity demand. In other words batteries look as they will soon be the cheapest way of smoothing out the peaks and troughs in daily electricity markets.

Lithium ion batteries may be the right choice for use in cars and other applications where space needs and weight are important considerations. In other circumstances, different battery technologies may well dominate. The Californian company Imergy has just announced a deal to sell 1,000 30 kW/120 kWh systems for rural electrification projects in India in combination with SunEdison, a solar PV provider.

Imergy provides a vanadium flow cell battery which beats lithium ion on longevity, ease of use and safety. The company promises an almost infinite number of daily cycles of filling and emptying with electricity and very high levels of reliability. What about cost? Imergy has said it hopes to get to $300/kWh but the Indian deal is not yet at that price.

An Imergy 30 kW/120 kWh battery. About 6m long

Like many other battery start-ups, Imergy’s cost improvements come from reductions in the cost of making the cells. Instead of using very expensive newly mined vanadium, Imergy is extracting the element from steel slag and other waste products. The company’s claim is that this reduces the cost of vanadium by 40%, making a substantial difference in the total cost of producing the battery.

Other young companies are promising equally striking costs. Eos Energy Storage caught attention by saying its containerised zinc hybrid cathode batteries are costing around $160/ kWh already. Eos says it reaches this extraordinarily low figure by using low cost chemicals and very simple manufacturing processes.

An illustration of the inside of an EOS 1 MWh containerised battery

Sakti3 hasn’t been so free with its cost estimates but does promise a power density of over 1,000 watt hours per litre of battery capacity. This is over twice what Tesla is currently achieving and suggests that the company might have costs already below $200/kWh. The CEO recently claimed to Scientific American that her company would ‘eventually’ hit $100/kWh. At that price, electric vehicles would probably be as cheap as petrol engine cars to build. At that’s before including the lower cost of refuelling with electrons rather than oil. (Dyson recently invested in this company).

Alevo, a Swiss/US company claiming to have raised over $1bn in funding, has just launched a containerised battery system that will sit on the edge of electric grids, helping to stabilise the frequency of the alternating current. It recently announced sales of 200 MWh of capacity to a company providing support to grid operators across the US. Commentators talk of this company arriving at $100/kWh within a few years.

Several Alevo batteries in standard containers

In time, we’ll see many of the claims from battery companies evaporate. The batteries may be more expensive, less easy to maintain and have shorter lives than their developers claim. But across the world the improvements in cost and performance in a wide variety of different companies suggest that battery costs, for both large scale containerised solutions and for electric cars, will continue to fall sharply.

The implications of this cannot be overestimated. In reliably sunny countries, it means that ‘solar+storage’ will become the lowest cost source of energy. National distribution grids may never be built. In countries with large numbers of personal cars, the switch to electric vehicles will speed up. Batteries will also provide much of the need for flexibility in adjusting supply of electricity to demand during the course of the day.

Cost reductions will encourage the growth of battery systems on domestic and factory premises, particularly in countries with big gaps between the price homeowners pay for electricity and what they get when they export power back into the grid. The need for ‘peaker’ power plants that work a few hundred hours a year will decline. The whole electricity grid will become more manageable.

How far are we away from large stationary batteries being financially viable in the UK? Let’s take the Imergy 30 kW/120 kWh hour system as a case study and assume it is priced at $300 a kWh. The unit therefore costs about £36,000 or £24,000.

In the UK’s recent capacity auction, an Imergy battery could have earned just under £600 a year for being ready to provide power at peak time. It could also be used to buy electricity at the daily minimum price of around 3p a kWh and sell it at the typical maximum of 7p or so. Assuming a round trip efficiency of 75%, that’s a profit of around £1,000 a year. In addition, if the battery was sited appropriately it could make money from grid frequency stabilisation payments and from reducing the payments for peak needs for large users. These numbers will all tend to get bigger as grid decarbonisation proceeds. There’s no goldmine here but returns of 10% a year look possible as long as Imergy’s promises of very low maintenance bills are delivered. Not exciting, but good money in a period of low to negative interest rates.

Even people in the energy industry in the UK still don’t understand how fast battery costs are falling and how quickly energy storage will become a new ‘asset class’ for return-hungry capital to invest in. We’re roughly where solar PV was five years ago just as the steepest decline in panel manufacturing costs started.

Batteries don’t solve the need for seasonal storage in high latitude countries – that requires a ‘power-to-gas’ solution – but within a decade they will have radically changed how the UK and other countries provide daily stability to the electricity grid. In sunny countries, they will be life-changing for a billion people.